This is an earlier version of an essay now published in Goddesses in World Culture, Volume 2. (Patricia Monaghan, editor. Praeger 2010). The version here does not have the footnotes, but it has the same quality of research. The author Dr. Claire French would like it known that the footnotes in the GWC version are not correctly placed, in case you read that version.

The Mountain Goddess of the Alps is known by many names: Raetia, Samblana, Nossa Dunna delle Glisch (Our Lady of the Glaciers), Matreia, Madrisa, Dea Noreia, Dana, Tanna, Bona Gaia, Verena, Veldidina, Donna Kenina, Donna Dindia, White Lady, and the goddess manifesting as Our Lady, and the Three Holy Virgins known as Margaret, Catherine and Barbara, or Ambat, Cubet and Borbet. She is still revered under the guise of other female saints throughout the Alps. Her sanctuaries include wayside shrines and chapels, usually built on pre-Christian sites of worship.

The Mountain Goddess of the Alps is known by many names: Raetia, Samblana, Nossa Dunna delle Glisch (Our Lady of the Glaciers), Matreia, Madrisa, Dea Noreia, Dana, Tanna, Bona Gaia, Verena, Veldidina, Donna Kenina, Donna Dindia, White Lady, and the goddess manifesting as Our Lady, and the Three Holy Virgins known as Margaret, Catherine and Barbara, or Ambat, Cubet and Borbet. She is still revered under the guise of other female saints throughout the Alps. Her sanctuaries include wayside shrines and chapels, usually built on pre-Christian sites of worship.

The question of the identity of the original Alpine settlers is a subject of scholarly dispute. Some contend that the area was settled by immigrants from the Altai mountains of central Asia, while the southern slopes of the Alps and the left shore of the Po were inhabited partly by Etruscans, Veneto-Illyrians, and the enigmatic Raetians. On the northern and western slopes the Celtic tribes were prevalent in the Cottian Alps in eastern Gaul. In the Upper Rhine and Danube valleys lived the Celtic Helvetians in present-day Switzerland, and the Norici and the Vindelici in what is now Austria and Bavaria respectively.

But by etymological comparisons, Swiss linguists Linus Brunner and Alfred Toth (1987) have theorized that the very earliest Alpine pastoralists came from the eastern Mediterranean and spoke Akkadian, an ancient Semitic language. The name Alp(pl Alpen) is said to be derived from Akkadian aleph, the bull. In the same language the word apuhas the meaning of shepherdess. (My shepherdess!was also the liturgical form of address for the Goddess Inanna). According to Brunner and Toth, the settlement of the Alps occurred over several millennia, beginning in the fifth millennium BCE after the last Ice Age. As Semitic loan words in Alpine pastoral and dairy industries show, these immigrants seem to have come from Mesopotamia , probably from the area of Ur. These settlers brought with them the cultivation of wheat and barley, as well as dairy farming, sheep breeding and bee keeping.

Their Goddess Raetia, the Lady Shepherdess retained her role as Lady of the Beasts. Innumerable sagas and legends describe her as protector of the Alpine fauna, particularly of chamois and ibex. She watches the hunter, often in her triple manifestation as the Saligen Fräulein (the Blessed Ladies), and any hunting crime is severely punished. She also protects the dangerous work of transhumance, the droving of cattle and sheep from winter quarters to summer pastures. It was this alpine invention that guaranteed the survival of human and beast in the Alps for thousands of years.

The Alpine Arc extending over 80,000 square miles over the centre of Europe from Slovenia to France cuts the continent into two halves and represents a considerable hindrance for trade and traffic. The glacier region of the Inner Alps, however, appears like an unexplored continent, a literal and figurative “white spot” on the map of Europe. Poor in economic assets, the region is nevertheless rich in natural beauty, history, and cultural values. After many armed conflicts in the past, the mountains are now peacefully shared by Latins (French, Italians, Romanches and Ladinians), Teutons (Bavarians and Suebians) as well as Slavs (Slovenians), and the mountain dwellers consider themselves a race apart. Although they speak different languages and have different religious denominations, there is an overall sense of unity and a social sense of common interests.

Regardless of their ethnicity mountain people learn from childhood that Nature is stronger than humans. Constantly aware of their own insignificance in relation to elemental forces and the many dangers of nature, they develop exceptional endurance and courage, and strong religious feelings. Their hard and often dangerous work has taught them that death is always close.

Apart from localized mining activities Alpine dwellers have contented themselves for centuries with subsistence farming and pastoral activities. They maintain their vast herds of sheep, goats and cattle by extensive transhumance to summer pastures called Alm (pl Almen), which in most cases can be reached only after many days of droving. There is a marked difference in population on the valley floors, in the foothills and on higher altitudes, where the earliest strata of population have retired before the Teutonic immigration in the Middle Ages.

Religious Life in the Area

To judge from the numerous shrines and sanctuaries dotted all over the mountains, the Alpine population must count among the most pious in Europe. Yet theirs is a kind of nature religion, based on the earth and rocks, fire and water, trees and animals. Their shrines, often built in the most inaccessible sites, are usually dedicated to Mary or other female saints. Archaeological finds of pre-Christian cultures are relatively rare. Anextensive study by Ludwig Pauli, The Alps, Archaeology and Early History (1984) however mentions some rare prehistoric finds pointing to early religious activities: a few female figurines of the Venus of Willendorf type from the Upper Palaeolithic found in the cave Barma Grandenear Ventimiglia in Liguria and a recently discovered bone tablet representing a woman with accentuated pudenda, found in the rock shelter of RiparoGabanat Martignano, Trento Province, a shelter inhabited from 4500–3500 BCE. But pride of place among archaeological finds must be accorded to the cult wagon of Strettweg in Styria. This is a small effigy of the goddess who seems to bless a young couple surrounded by warriors and stags, dated to between the eighth and fifth centuries BCE.

The Alps have been continuously inhabited for 10,000 years, yet the earliest human finds go back 50,000 years when Ice Age hunters stalked cave bears and left bear skulls and bear bones in the Drachenlochin the Swiss Canton of St Gall and in other caves which were once held sacred. In later centuries votive deposits became more frequent in the vicinity of important passes from Italy to Switzerland such as at St Gotthard and St Bernhard, at the Stilfser Joch, and at Mitterberg near the Grossglockner, in the Salzburg region. Other preferred places for sacrificial deposits were wells with medicinal qualities, lakes such as Lake Neuchatel and the confluence of rivers. A well near the Achensee in Tyrol yielded several votive plaques offered by women to the sacred twins Castor and Pollux praying for safe confinement. Innumerable artefacts and hieroglyphs point not only to hunting methods, but also to religious practices.

It is now generally recognised that most early Alpine tribes had a matriarchal and matrifocal organisation. They worshipped a Goddess under different names and different manifestations. This was originally the Earth Goddess, in her manifestation as nubile young one/virgin in Spring, mature woman and mother in Summer, and death goddess in Autumn and Winter. Her consort was an earth spirit, the wild man or green man, a disguised youth who still appears in some places during Alpine Spring celebrations. Over the millennia the persona of the Goddess has changed considerably, yet even Christianity was unable to completely obliterate her image and absorbed it in the form of Mary, St. Anne (mother of Mary), and the trinity of the Three Holy Virgins (Catherine, Margaret, and Barbara).

The Goddess Raetia, Protectress of the Alpine Pastures

After the Roman conquest of the Alps, a better knowledge of Alpine culture and religion can be traced. Writers of antiquity called the people of the Alps “Raetians”, after their tribal goddess Raetia, Reita or Reeta. He had her central shrine at Este in the valley of the Po River. In addition to Raetia, the name Esti (Estu) occurs, possibly another name or title for Raetia related to the Akkadian Ishtar. In Celtic Noricum, the protective divinity was Dea Noreia, after whom their city was named.

After the victory of Drusus and Tiberius over the Alpine tribes the whole area from the Po Estuary to Lake Constance was established as Provincia Raetia. At that time the Alpine region was still largely unknown to Roman administration and relatively sparsely populated. To be posted there was regarded as a punishment because of the wild aspects of the region and its harsh climatic conditions. Rome only maintained small military units for securing the roads to the Northern and Western provinces of the empire and for the most important mountain passes.

Through phonetic changes particularly in the Swiss regions of Tessin and Grison, the name of the tribal Goddess Raetia or Reisa changed to Risa, Madrisa/Matreia, or Mother Risa. Many place names throughout the Alps are composed with the name Reita, Risaor similar formations.

Remnants of Goddess Worship in Raetian Switzerland

The authority for the Swiss Grison region is Mgr Christianus Caminada (1876–1962), Bishop of Chur, the son of a mountain farmer. His book Die verzauberten Täler (2006) is a good introduction to Swiss nature religion. Caminada describes Saint Margaret (Margriata), a name that may have evolved from Raetia, Reita orRisa.In the Romanche language, an amalgamation of Latin with the pre-Latin local idiom, her name was Songt Margriata with phonetic affinity to the word Raetia. Like the Goddess Raetia in antiquity, Songta Margriata was the unseen protectress of the Alm,the Summer pasture where cows, goats and sheep are milked and cheese is produced according to age-old rituals. The head shepherd and cheese maker is called the Senn and like the captain of a ship he has absolute authority over human and beast.

According to an ancient rule, the Alm is (or used to be) strictly off limits for women. Yet the ancient Swiss folk song “Canzun de la Songta Margriata”, recorded by Caminada, tells of a beautiful woman called Margriata who is discovered on the Alm by the youngest shepherd boy. She pleads with him not to tell the Senn of her presence.With every stanza she promises him ever-greater treasures if he will not betray her. But he does not listen and runs to tell the Senn of the beautiful woman he has discovered. To her great regret Songt Margriata must leave the Alm forever, taking her blessings with her. The mysterious woman is the Goddess Raetia in her late manifestation as protectress of the mountain pastures.

Caminada was so moved by the melody of the song, which he acquired by taping an old woman’s performance, that he had it analyzed by Swiss musicologist, Fr Ephrem Omlin of the Monastery of Engelberg. Without actually declaring the song of pagan origin, Omlin certified that it had definite affinities with pagan liturgical music and must be much older than medieval hymns. After this verdict Caminada suggested that it be sung at special occasions as the national hymn of the Raetian cantons “standing upright and with hat in hand”.

Eduard Renner, in his book Golden Ring above Urion Raeto-Romanche folklore (1991), quotes an ancient Alpine evensong or blessing, which must be performed each night by the Senn for the protection of the Alm,its shepherds, and the cattle. Using a large milk funnel as a megaphone he sings a long prayer over the pasture, ending each stanza with the refrain:

Around this pasture there is a golden ring,

And there sits Maria with her dearest little child…

The prayer has many verses and is accompanied by a symbolic gesture signifying a “ring pass not” spell over the Alm. This ritual blessing is also quoted by Hans Haid in his book Mythos und Kult in den Alpen(1992b). Haid adds that without the change of “Marisa” to “Maria” it would have long been prohibited by the Church authorities.

The Many Manifestations of the Mountain Goddess

Many other names can be found for the Goddess of the Alps, over time and beyond the realm of Raetia. The name of the ancient European Goddess Dana, (from De Ana orAnu) mentioned in the Irish Book of Invasions, can be found in the hamlet of Danay, at an altitude of 2000 metres above sea level in the glacier regions of the Alpine watershed. Other names known from the legends of South Tyrol are Tanna, Samblana, Bona Gaia, Donna Kenina, and the White Lady. On the northern slopes of the Alps, Frau Berchta is commemorated in the name Berchtesgaden.

The Goddess also appears in her triple form of die drei Saligen Fräulein(“the three Blessed Ladies”) Ambet (Aubet), Cubet and Borbet, later changed into the three Christian virtues Faith, Hope and Charity, or the triad of Christian saints Catherine, St. Margaret and St. Barbara. The effigies of these three holy virgins adorn most Alpine churches, particularly in Catholic Austria and Bavaria. School children learn to distinguish them by their attributes:

Sankt Margareth mit dem Wurm St Margaret with the worm (the dragon)

Sankt Barbara mit dem Turm St Barbara with the tower

Sankt Catharine mit dem Radl St Catharine with the wheel (the sun wheel)

Das sind die drei heiligen Madl. These are the three holy lasses.

On the eve of the sixth of January, Epiphany and Feast Day of the Three Wise Men, the farmers smoke the house with burning herbs and write on the lintel of each door the initials of the names of the three Magi/sages: Caspar, Melchior, Balthasar, thus: C + M + B. But it is well known that the letters actually refer to Catherine, Margaret and Barbara.

Dana, Tanna, Sam-Alu-Ana

The hamlet of Danay consists of a few chalets and stables at the northern end of the Matsch Valley, a point which marks the watershed between southern and northern Europe, at an altitude of 1500 meters. Twice a year in Spring and Autumn, a team of shepherds drive thousands of sheep past the hamlet, using it as a resting place on their long and exhausting trek. They come from the fertile southern valleys to pasture their flocks, the communal property of hundreds of farmers, on the grassy plains of the northern Alpine slopes. Each year before their long trek over the glaciers, they have to swear an oath to protect the animals with their lives, to milk the cows and produce butter and cheese according to the ancient customs.

In close proximity to the hamlet there exist several shrines of pilgrimage, Catholic mountain sanctuaries dedicated not to the Holy Virgin, but to Saint Anna, a name close to that of the Goddess Anu (Dana). Most researchers agree that the shrines are of pagan origin, and before Christianisation were dedicated to De Ana or Anu, Dana, the ancient European goddess originally worshipped by the Pelasgians, then by the ancient tribe of Ireland Thuata de Dannaan. According to an Irish glossary Dana was worshipped as The Mother of the Gods.She is found in the Alpine watershed as well as in ancient Ireland. The Danube, the Dnieper and Danemark are named after her. In the same area archaeologists have discovered two prehistoric light beacons, numerous palaeolithic remnants and recently the grave of Ötzi, the Man in the Ice.

Originally a Mediterranean goddess, Dana was likely introduced to Central and Western Europe by Pelasgian refugees, who fled advancing Dorians on the Balkans. Locally, the name Dana was pronounced “Tanna”. She was a goddess of glaciers with a heart of ice whose throne can be found on the highest peaks. She wore a mantle of snow and a crown of blue ice. Her closest subjects and helpers were the fearsome Croderes,elementals without a human heart, who carried out her orders. These nature spirits had power to save or destroy the valley floors with avalanches, mudslides, falling rocks and raging torrents.

Legend tells that Tanna was once in love with a prince from Aquileja by whom she had a son. To the fury of the Croderes she renounced her crown of ice, and taking pity on humans, she forbade the destructive work of the elementals. When she discovered that the prince had betrayed her, she returned to the mountain peaks and ordered the Croderes to resume their work, wreaking worse havoc in the valleys of humans than ever before.

It is also said that Tanna possesses a magic mirror of glistening ice, which allows her to watch the works of humans. She collects the souls of babies who die before baptism and keeps them under her mantle of ice and snow. The Alpine population has always seen a great unfairness in the Christian teaching that unbaptised children can’t go to heaven. There are several places of pilgrimage where the unfortunate parents take there stillborn and/or unbaptised babies and deposit them on the altar in the desperate hope that the infant may give a faint sign of life and hence can be baptised. It is said that the winter goddess Tanna takes pity on them and favours especially little girls to carry her long train of ice and snow.

Two little girls that the Ladinians of the Dolomites call les yemeles, (“the twin girls”) are in Tanna’s service. Lonely wanderers may meet them on dangerous mountain paths. They warn humans of threatening blizzards, avalanches, rock falls and other mountain dangers. Many legends show that Samblana and Tanna are different aspects of the same goddess. She is the divine queen of the glacier region, the realm of eternal ice, but she still has a motherly heart for children.

The Curse of the Mountain Goddess

In the vicinity of the Danay hamlet, legend tells of the accursed city of Tannanneh. Its rich burghers had hearts of stone and never gave alms to the poor. Once, an old beggar who had been chased from their doors cursed the city with the words:

Tannaneh, Tannaneh, Tannaneh, Tannaneh

Es schneibt an Schnee It will snowa snow

Der apert nimmermmeh! Which will never melt again.

And so it happened. Tannaneh vanished under a thick cover of snow and was never found again. Other legends tell about accursed farms or townships whose inhabitants were punished for their sins. Upon investigation these legendary places usually turn out to have been pagan shrines condemned by the church. Perhaps Tannaneh, as the name suggests, was such a sanctuary dedicated to Tanna.

The Goddess and the Man in the Ice

The Goddess of the Alps is connected with the discovery, two decades ago, of homo tyrolensis,the “Man in the Ice” nicknamed Ötzi because he was found at a glacier of the Ötztal, on the Austro-Italian border. Discovered by tourists on September 19, 1991, the Man in the Ice became a cause celebre. Although situated in the geographic centre of Europe, the locality of the find is so remote and the border between Italy and Austria so ill defined that the discovery almost provoked a diplomatic conflict.

It was initially assumed that the man had been the victim of murder or misadventure, leading to the transport of the body to the Innsbruck coroner. This was badly mishandled, from the archaeological point of view; and only when it was discovered that the man had been in the ice for 5000 years was he transferred to the archaeological team of Innsbruck University. When X-rays revealed that a stone arrowhead was found lodged under the shoulder of the body, a colourful murder story was concocted, which the media enjoyed. Yet a number of pertinent questions were not answered: none of the official publications referring to the glacier mummy noted that the man lived in a society where human sacrifice in honor of the goddess was most probably practiced. This connection was first pointed out by German ethnologist Heide Göttner-Abendroth (2002). She suggests that the man’s final resting place beneath the sacred mountain throne Similaun would almost certainly point to a human sacrifice. Human sacrifices were offered yearly until relatively recent times. In the case of the Ice Man his death may have been staged as a hunting accident.

Since the discovery of the Man in the Ice, the name of the nearby glacier, the Similaun, has been the subject of folkloric and etymological studies. The name Samblana is associated with the Similaun glacier. According to Kurt Derungs, the mountain’s original name was Sam-Alu-Ana,which translates assam (“white”) alu(“deity”) and Ana (the name Anna). The same name occurs in the Himalayas where a peak close to Mount Everest is called Ana-Purna.The name Similauntherefore signifies White Goddess Ana,a name befitting this beautiful glacier.

Hans Haid, who lives in the region of the discovery site Ötztal,concludes that Ötzi may have been a shepherd priest or a shaman. This can be inferred from his elaborate netted mantle, his feather-lined shoes, and the magical tools and hallucinogenic mushrooms found in his pouch. Either voluntarily or by the verdict of his tribe he must have suffered a sacrificial death. His burial place beneath the Similaun, literally at the feet of the goddess Samblana, suggests that he was to be especially honored in death.

The Kingdom of Fanes

If the Canzun de la Songt Margriata hides the connection with the Mountain Goddess for the people of Grison in Switzerland, the story of The Kingdom of Fanesserves the same purpose for the Ladinians of the Dolomites in Italy. This saga was discovered and saved from oblivion by Karl FelixWolffof South Tyrol, a dedicated collector of folk customs and sagas of the Dolomite valleys. His collected works appeared under the title Dolomitensagen(1974) and have since been often reprinted in German, Italian and English. At the beginning of the 20th century Wolff postulated a matriarchal organisation for the valleys of the Dolomites and their Ladinian (Raetian) population.Having been denied a college education he was accused for decades of inventing his material, and the authentic sagas he published were long regarded as fabrications. Only towards the end of his life did he find recognition and was awarded an academic medal by the University of Innsbruck. Wolff reconstructed the story from the fragments he and his friend Hugo von Rossi had collected in the Dolomite valleys of Ampezzo and Fassa.

In the tale, a strange woman called Molta gives birth to a little girl on a mountain peak and dies. The infant is adopted by an aguana, an old wise woman who calls the child after her mother, Moltina. Moltina grows up among marmots, learning their ways, their language, and their salute to the morning sun. She finds she has the power to change into a marmot. She marries a prince from a foreign country and having given asylum to a tribe of refugees, Moltina and Prince Landro found the Fanes Realm. Moltina is revered as queen and founding mother of the kingdom and the marmots are the realm’s secret totem. The people of Fanes live happily and in peace for many generations.

There comes a day when a queen of Fanes marries a king who disturbs the old order of the queendom. He first woosthe queen’s sister Tsikuta, a priestess, and fathers a son with her, before turning his attention to the queen. The king abolishes the marmot totem and introduces the totem of the eagle. The queen does not protest. To his disappointment she gives birth to twin girls, Dolasilla and Luyanta. Luyanta is presented as a totem exchange to the marmot people. Dolasilla grows up to become a famous archer and warrior woman who wins many lands and great treasures for her father.

Eventually Dolasilla falls in love with her shield bearer Ey-de-net (Night Eye) and wants to marry him. Ey-de-net does not know that he is Tsikuta’s son and Dolasilla’s half-brother. In their matrilinear society, which insists on exogamy, their marriage would amount to the greatest crime. In vain Tsikuta tries to warn her son. The king has other reasons to fear the marriage. According to the mother-line, Dolasilla is the rightful heiress of the realm, as her daughters would be after her. In order to secure the crown for his younger son with the queen, the king sends Ey-de-net into exile. In his greed, the king plans he wants to win the goldmine Aurona in the Padon mountain and for this purpose is prepared to betray his own people. Dolasilla is killed in battle. The wicked king is changed into stone and the realm falls into ruin. Luyanta, who had been living with the marmots, reappears to lead the remaining people into the caverns of the Fane Mountains, where they turn into marmots.

Ulrike Kindl has analyzed this story as a tragedy of ancient Mother Right, in Kritische Lektüre der Dolomitensagen von Karl Felix Wolff, Volume II (1997). Apart from the marmot totem, she found many other ancient features in the story. One of them is the queen’s friendship with a vulture who breathes a blue flame and keeps alive the memory of fallen heroes. Kindl points out that the story must be understood in the light of the demise of matrifocality and exogamy, in favour of the patriarchal attitudes and male lineage represented by the king. Under patriarchy the marriage law of exogamy (young women marrying men from outside their tribe) changed into endogamy (marrying within the tribe). As long as there was no land property to share it was better for the tribe to bring in genetic biodiversity via exogamy and property was irrelevant. When land became more valuable young women were forced to marry within the tribe in order to keep the tribal land property whole and undivided.

The heroine Dolasilla with her silver bow and arrows represents the goddess in her virginal state. Her thirteen magical arrows, one of which kills her, represents the thirteen months of the lunar year. When she changes into a nubile woman her chosen hero Ey-de-net, whose name connects him with the moon, is unsuitable because he is of the same totem, hence her brother. Their marriage would represent incest. Ey-de-net’s mother Tsikuta, who always wear red and carries red poppies, represents the goddess in her Summer aspect. When the king’s betrayal hastens Dolasilla’s death and the ruin of the realm, her sister Luyanta appears as death goddess to lead the vanquished people into the mountain caves. In this story it is first the figure of Moltina, then Tsikuta, later Dolasilla and finally Luyanta, her alter ego,who display characteristics of the Alpine Goddess.

A Continuing Tradition

To say that the people of the Alps still worship a Goddess would be an exaggeration. However, it cannot be overlooked that most of their churches and sanctuaries are dedicated to Our Lady in her various guises. Whole countries and regions, like Austria, Bavaria, and the Tyrol placed themselves under her protection, and soldiers’ prayers before battle are addressed to Her.After WWII it was not unusual for mothers to dedicate statues of the Mater Dolorosa in thanksgiving if their sons had safely returned home. Famous shrines like Altötting in Bavaria and Maria Einsiedeln in Switzerland are proud of their Black Madonnas, effigieswhich have pagan connotations. All this seems to betray a preference for maternal values that can be traced back to pre-Christian times.

From the proto-European Dana to Saint Anna of today, the Great Mother in her many manifestations, there was never a time without a Mountain Goddess in the Alps, nor a mountain peak that was not sacred to Her.Today the mountain dwellers place their faith in Our Lady and the Three Holy Virgins, but no matter how much Christianity has tried to chase her away, and erected large crosses on mountain tops, the Mountain Goddess still resides in the Alpine mountain peaks, her aura magnificently apparent, and her ancient cult places may be approached with the same reverence that is accorded any place of worship.

(c) Claire French

Bibliography

Brunner, Linus and Alfred Toth. 1987. Die rätische Sprache enträtselt. St Gallen, Switzerland: Amt für Kulturpflege des Kantons St Gallen.

Caminada, Christian. 2006. Die verzauberten Täler: Die urgeschichtlichen Kulte und Bräuche im alten Rätien.(The enchanted Valleys). Chur, Switzerland: Desertina. Originally published 1961. Olten u. Fribourg/Breisgau: Walter Verlag.

French, Claire. 2001. The Celtic Goddess: Great Queen or Demon Witch?Edinburgh: Floris Books.

French-Wieser, Claire. 1975. Das Reich der Fanes – eine Tragödie des Mutterrechts (The Fanes Kingdom – a Tragedy of Matriarchy).Der Schlern49: 4–12.

French-Wieser, Claire. 1999. Mutmassungen über den Namen “Danay“(Musings about the name “Danay“).Der Schlern73/3: 183–187.

French–Wieser, Claire. 1999.Mythische Wurzeln in Volksmärchen und höfischer Epik (Mythical Roots in popular Tales and Court Epic). Der Schlern73/12: 759–764.

Göttner-Abendroth, Heide. 1995. The Goddess and her Heros.Stow, MA: Anthony Publishing Company.

Göttner-Abendroth, Heide.2002.“Auf den Spuren der Göttin” (In the Wake of the Goddess).Planet Alpen 8: 13–40.

Göttner-Abendroth, Heide. 2005.Frau Holle – Das Feenvolk der Dolomiten. Königstein/Taunus: Verlag Ulrike Helmer.

Haid, Hans. 1992a. Aufbruch in die Einsamkeit (Start into Solitude). Rosenheim, Germany: Rosenheimer Verlagshaus.

Haid, Hans. 1992b. Mythos und Kult in den Alpen (Myth and Cult in the Alps). Bad Sauerbrunn, Germany: Edition Tau.

Haid, Hans. 2006. Mythen der Alpen (Myths of the Alps). Vienna:Böhlau Verlag.

Kindl, Ulrike. 1997. Kritische Lektüre der Dolomitensagen von Karl Felix Wolff, Volume II. San Martin de Tor: Istitut Ladin “Micurà de Rü”.

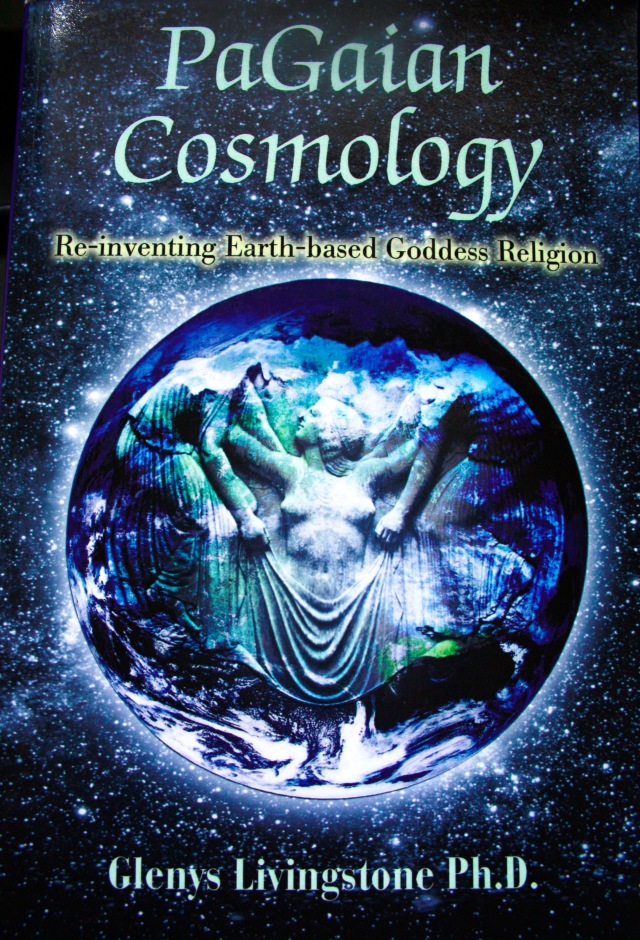

Livingstone, Glenys. 2005. PaGaian Cosmology. Lincoln NE: iUniverse.

Pauli, Ludwig. 1980. Die Alpen in Friihzeit und Mittelalter: Die archaologische Entdeckung einer Kulturlandschaft.Munich: Beck Verlag.

Pauli, Ludwig. 1984. The Alps, Archaelogy and Early History. London: Thames and Hudson.

Renner, Eduard. 1991.Golden Ring above Uri. Zurich: Ammann Verlag.

Wolff, Karl Felix. 1974. Dolomitensagen. Innsbruck: Tyrolia Verlag.

Wolff, Karl Felix. 1958.The Dolomites and their legends. Innsbruck: Verlagsanstalt Tyrolia.

DR. CLAIRE FRENCH was born in 1924 into a family of South Tyrolean sculptors and studied modern languages and literature at Innsbruck and Melbourne universities. Her doctoral thesis (in Women’s Studies 1989, Australia) was a study of the mythological background of the Welsh Mabinogion, particularly with regard to the role of the Celtic Goddess in Her different aspects. It was published in 2001 inEnglish under the title The Celtic Goddess, Great Queen or Demon Witch, by Floris Books at Edinburgh, and in German (2001) by Edition Amalia at Bern, under the title Als die Goettin keltisch wurde (When the Goddess became Celtic). Claire migrated to Australia in 1951, where she married and has three children. From 1965 to 1995 Claire was a lecturer with the Melbourne Council of Adult Education, initiating courses in European Cultural Studies, Women’s Studies, Spirituality and Celtic Studies. She also contributed lectures and workshops to the C.G. Jung Society of Melbourne – many directly addressing Goddess. In 1993-94, Claire taught a series on GAIA. She has published extensively about goddess mythology both in English and in German. Dr. Claire French passed from this life in April 2020. Her autobiography is Meine Verkehrte Welt; and the English version is available here: My Upside Down World

DR. CLAIRE FRENCH was born in 1924 into a family of South Tyrolean sculptors and studied modern languages and literature at Innsbruck and Melbourne universities. Her doctoral thesis (in Women’s Studies 1989, Australia) was a study of the mythological background of the Welsh Mabinogion, particularly with regard to the role of the Celtic Goddess in Her different aspects. It was published in 2001 inEnglish under the title The Celtic Goddess, Great Queen or Demon Witch, by Floris Books at Edinburgh, and in German (2001) by Edition Amalia at Bern, under the title Als die Goettin keltisch wurde (When the Goddess became Celtic). Claire migrated to Australia in 1951, where she married and has three children. From 1965 to 1995 Claire was a lecturer with the Melbourne Council of Adult Education, initiating courses in European Cultural Studies, Women’s Studies, Spirituality and Celtic Studies. She also contributed lectures and workshops to the C.G. Jung Society of Melbourne – many directly addressing Goddess. In 1993-94, Claire taught a series on GAIA. She has published extensively about goddess mythology both in English and in German. Dr. Claire French passed from this life in April 2020. Her autobiography is Meine Verkehrte Welt; and the English version is available here: My Upside Down World

You must be logged in to post a comment.