Story telling.

For better and for worse, todays information sharing technology makes it so much more evident that the human race is primarily a story telling species, everything we do and say, all our thinking and behaviour is almost entirely influenced by the stories going on between our ears, be they fact or fiction, be they well intended or otherwise, stories are our primary and most influential source of information. So, it is with this grand philosophical premise in mind that I offer you My Uluru story – Ngayuku puli-pulka tjukurpa, this by way of celebrating NAIDOC 2021, here on the traditional land of the Wakka Wakka people (S.E. Queensland Australia).

This is a story of how I was literally re-minded by such a remarkable place – Uluru, and its indigenous custodians – the Anangu, about the importance of our relationship to place and family – walytja or kin. Thanks to its indigenous Anangu custodians, over millennia the landscape and rock formations of Uluru Kata-Tjuta National Park has invoked stories cum lessons that I believe are of potential value for the whole human race, especially now that our relatively advanced information sharing technology is being deliberately used in so many subtle and not so subtle ways to divide and separated us from our sense of place, from each other and all too often, from reality.

‘Uluru-Kata Tjua National Park, an isolated tiny patch in Australia’s vast arid zone at the very centre of the continent, is the symbol for a special, almost intangible quality of the continent’s interior but also for the co-operative human spirit. It is one of the most remarkable places on earth. From the start I was determined to find out as much as I could about it’.

Uluru Looking After Uluru Kata-Tjuta ~ The Anangu Way

Stanley Breeden 1994.

Life among the Anangu.

From 1990 until 1995, it was my privilege to have lived and worked with the indigenous Anangu of Central Australia (Northern Territory) at Uluru Kata-Tjuta National Park and then from 1995 until 1998 on the Anangu Pitjantjatjara Lands (South Australia). Uluru Kata-Tjuta is a World Heritage Area National Park, listed for both its natural and cultural values. During my time there I had the rare opportunity of being able to work closely with its Anangu custodians while re-nominating the park for World Heritage Area listing based on its cultural values, it was already WHA listed based on its natural values. During the same 1990-95 period, Anangu and Piranpa park staff along with various professional consultants and builders worked on the design and construction of the Uluru Cultural Centre. The early 1990s was when the award winning author of natural history Stanley Breeden was given permission from Anangu to produce a book about the park, particularly about the nature of the park, its flora and fauna, but also about the Anangu and Piranpa – whitefellas, who were working together to manage Uluru ‘the Anangu way’. This too was a most valuable opportunity for Stanley and us Piranpa park staff to learn more about the depth of knowing about and relatedness to their place that Anangu possessed.

‘We commend this book to you, and affirm its accuracy and value. We Anangu are strongly committed to our culture, and we believe this book shares in our commitment’

Tony Tjamiwa – Traditional Owner in forward to the book –

Uluru Looking After Uluru Kata-Tjuta ~ The Anangu Way

(Stanley Breeden 1994).

I believe I can safely say that for most if not all park staff the period 1990-95 was a particularly valuable period to have been living and working at Uluru, it was a time when the Anangu traditional owners were settling into the management of their sacred land which had been formally and conditionally returned to them by the Australian Commonwealth Government in 1985. The condition of return being that the park would immediately be leased back to the Commonwealth for 99 years. Nevertheless, the following decade was a particularly productive period during which the leadership of tjilpi – senior Anangu man, Tony Tjamiwa and his Piranpa liaison officer Jon Willis enabled Anangu to become more confident, assertive, capable and generous in expressing the more public and appropriate for sharing components of their Tjukur(pa) – their Lore. This was also a significant period when a new emphasis on sharing Anangu Tjukur(pa) and culture was in effect a maturing of the relatively early days of ‘joint management’, that is the management of the park by both the Australian Nature Conservation Agency and the parks Anangu traditional owners.

In addition to the above mentioned more prominent projects, several less publicised park management initiatives took place during this period, including placing a new emphasis on Pitjantjara language classes for us Piranpa staff. These classes were conducted by Anangu rangers and the few Piranpa staff such as Julian Barry and Jon Willis who were fluent speakers of the Pitjantjatjara language. As a result of these Anangu led language classes a healthy number of Piranpa rangers – mostly female I might add, became fluent Pitjantjara speakers, this too contributed significantly to the maturing of joint management. Another similar initiative was that of an Anangu led basic cultural training course cum certificate designed to enable visiting and local tour operators – particularly bus drivers most of whom until then were making up their own stories about the park and Anangu, to gain a more appropriate and approved understanding of the park and how it was now being managed, ‘the Anangu way’. While some bus drivers initially balked at the idea, at the end of such training sessions most of them had enjoyed their face to face interaction with Anangu and their better understanding of Anangu culture.

Back in 1994 I was highly motivated by Stanley Breeden’s chapter thirteen entitled ‘To climb or not to climb’ in which he writes –

‘Anangu find the compulsion to climb, to conquer, Uluru incomprehensible and also think that it shows disrespect by strangers for another people’s land.. They want people to understand Anangu and Uluru Kata-Tjuta. Understanding is everything. Once people understand, Anangu are convinced mutual respect will follow.

Tjamiwa expresses it.. We want tourists to learn about our place, to listen to us Anangu, not just look at the sunset and climb the rock..’

Nganana tatinja wia – we never climb, the Anangu traditional owners of Uluru Kata-Tjuta National Park reluctantly tolerated people being allowed to climb Uluru. Unfortunately, even though Anangu had made it very clear how they felt about the climb, the pressure from the tourist industry and to a lesser extent the Piranpa agency involved in joint management of the park continued to resist its closure for too long a period. For some years in my role as the senior Piranpa staff member, I advocated for the closure of the climb having made various unsuccessful submissions to my supervisors in Darwin and Canberra. On reflection, my persistence over this issue cost me too much lost sleep and a few casual friendships. However, about 25 years later on Sunday 26th Oct 2019 Anangu and probably millions of us Piranpa celebrated the closure of the climb at Uluru.

From my relatively well informed perspective – albeit decades later and from afar, the closure of the climb at Uluru in 2019 was a well overdue move in the context of managing the park ‘the Anangu way’. Uluru is now being respected and protected in a way that better reflects its universal significance as a sacred site.

‘It is directly and tangibly associated with events, living traditions, ideas and beliefs of outstanding universal significance, and it is a potent example of imbuing the landscape with the values and creative powers of cultural history through the phenomenon of sacred sites.’

Renomination of Uluru – Kata Tjuta National Park

Department of the Environment, Sport and Territories 1994

On reflection I often think about the eight years I spent in Central Australia with my then partner Marian Hill as a kind of pilgrimage. Our original intention was to experience what we thought might be ‘the real Australia’ rather than the sanitised version were were both immersed in an urbanised Victoria. Nowadays I do reflect on my time with Anangu in Central Australia as a pilgrimage into a time and place that gradually changed my mind, for the better and for ever.

Finding my own story stone.

My partner and I lived along with other Piranpa and the more permanent Anangu residents at a place called Mutitjulu, a small community within the park and just a few kilometres from the base of Uluru. Much of my recreation time was spent roaming and exploring the surrounding landscape and rock formations of Uluru and Kata-Tjuta. On one such occasion I stumbled upon what would eventually become my most influential symbolic story stone. Only after many visits and spending much contemplative time at its resting place did I eventually become sensitive enough to receive and relate to this stone as ‘ngayuku puli tjukurpa’ – my story stone. It is rectangular in shape with proportion similar to that of a standard matchbox and I estimated its weight to be close to a metric ton, far too heavy to have been moved by human hands. Therefor, I imagined it to have been shaken from its place of origin at a time when our Earth Mother – Gaia, was rumbling deep within her great Southern belly, probably in response to some powerful tectonic force. Since then and probably for millennia, it has rested on just two of its diagonally opposite edges, exposing itself to be observed, felt and related to through each of its six rustic faces. Almost three decades later my story stone continues to inspire me to imagine, study and write about the significance of relating to place at both the personal and cosmic levels. During such periods of contemplation I can imagine how the first Anangu hunters and gatherers, who having evidently produced some nearby cave art, received this impressive looking stone in their own unique indigenous way.

Once I felt comfortable about relating to my story stone in this way, it marked the beginning of the most creative personal journey of my adult life, a journey that released me from decades of entrapment in relatively ordinary, dominant states of consciousness, a journey that eventually reminded me of a time and place – Penarth, Wales 1944-50 the first five years of my life, when like many a young Anangu, I too was being nurtured by my mother to enjoy and cultivate our relationship with place, Self, other and all-that-is. The storying and importance of relatedness in general and relationship with family or kin in particular was literally brought home to me when a group of mapla tjilpi – friendly senior Anangu men, realised I had not been home to visit my kin for about 26 years – since leaving Wales in 1967, they thought I must be a bit sick in the head. Not long after this friendly shame job cum wake up call I returned home to Wales where I enjoyed relating to my family members – including young ones whom I had never met, in what for me was a new and healthier way. At the time I was in effect being reminded about and grown up by Anangu to the importance of my own Welsh place, heritage and kin.

‘Bob’s admiration for Anangu takes a somewhat different direction from that of the other Piranpa I spoke to.. He continues: “..I’m pretty sure that my upbringing had something to do with it. My mother was a very nice and gentle person who was close to nature, and she influenced me..”

Uluru – Looking after Uluru-Kata Tjuta~The Anangu Way (1994: p183)

Life back in mainstream Australia.

My story stone, and I are now physically separated by about 3,000 kilometres of mostly Australian desert landscape, to and from a place where it rests safely inside a small cave at the base of the northern face of Uluru in Central Australia. Nevertheless, since the year 2000 my story stone continues to inspire me to embark on exciting, new spiritual and political journeys.

One particularly influential story that came to me while living and working among the Anangu of Central Australia is about how and why it was not likely or even possible for Anangu men or women to form a centralised group within their tribe or community for the purpose of having power and control over the rest of the community. Prior to being colonised by European invaders who had already perfected such a practice, Ananguku tjukurpa – lore, their way of being and relatedness to place and other – including the other than human beings within their place, was such that there were no words in their Pitjantjatjara language that could so much as give rise to thoughts of power and control over each other, let alone the more extreme thoughts of forming a centralised group for such a purpose. Moreover, the initiation of young adolescent Anangu boys and girls into adulthood was particularly important for maintaining the level of maturity and cooperation that was essential for such indigenous hunter gatherer communities to thrive.

Such an extreme contrast between the forms of community, economy and productivity being practiced by the Anangu of Central Australia – prior to being invaded and divided, with that being practiced by their European invaders is a most pertinent and valuable story, not just for contemporary Australians but for the whole human race. Traditional Anangu society was a relatively free, cooperative and egalitarian society, when compared to their European invaders who were of a society that was deliberatively divided, unequal and mostly imprisoned. The indigenous Anangu of Central Australia had no need for standing armies, gunships or police forces, their relatedness to place and each other was demonstrably more mature, sophisticated and peaceful than that of their invaders. Unfortunately and maybe inevitably, in more recent times some Anangu leaders – usually men, have adopted their European coloniser’s practice of centralised power and control with a bit too much relish.

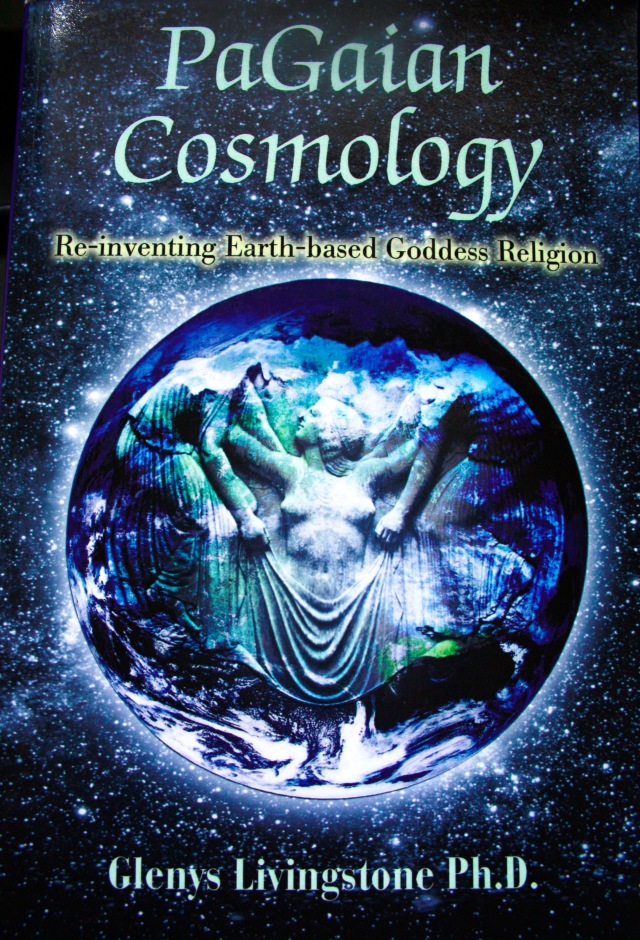

Not long after returning to live in main stream Australia, my Uluru experience aroused in me a new curiosity that soon had me doing some relevant academic study. In an effort to try and make some sense of what for me was an obvious and annoying lack of understanding and empathy toward the socio-economic circumstances of indigenous Australians among Australians in general, I enrolled to do a Social Ecology Masters degree at the University of Western Sydney (UWS). During my time at UWS I met another like minded story teller, Glenys Livingstone with her own emerging story, ‘PaGaian Cosmology – A Re-inventing of Earth based Goddess religion’. Glenys and I both graduated on the same day in 2003, Glenys gaining her Doctoral degree and me my Masters degree with a distinction. Several decades later we are still just as passionate about our storytelling together as we were on the day we met.

Since the year 2000, Glenys and I have been much inspired by the teachings of Thomas Berry and Brian Swimme both of whom authored ‘Canticles to the Cosmos’ 1990 and ‘The Universe Story’ 1994. Both of these works together with our ongoing practice of seasonal celebrations that are mostly informed and inspired by ‘PaGaian Cosmology’ 2005, – (the book form of Glenys’ doctoral thesis), have enabled us to deepen our appreciation of planet Earth’s biosphere as being an awesome creative event. ‘Canticles to the Cosmos’ is based on Thomas Berry’s twelve principles of a ‘functional cosmology’, principle number twelve convinced me that if we are to develop our full personal and human potential, we will need the emergence of something close to what Thomas describes as –

an ‘Ecozoic era of Earth development’, an era during which we ‘activate the inter communion of all the living and non living components of the Earth community..’

Such was my new found appreciation and experience of creativity and beauty throughout an otherwise increasingly troubled world, that it soon prompted me to search for a compatible political story. I had almost given up on my search and politics in general when I came across these two particular passages –

“In this world, at this point, no political revolution is sustainable if it is not also a spiritual revolution – a complete ontological birth of new beings out of old. Equally, no spiritual activity deserves respect if it is not at the same time a politically responsible, i.e; responsive, activity… The only meaningful political direction left now is synonymous with the only meaningful spiritual direction left now: towards the conscious re-fusion of the spirit and the flesh… This time it will be a global consciousness of our global oneness, and it will realize itself on a very sophisticated technological stage; with perhaps a total merger of psychic and electronic activity.”

Barbara Mor – ‘The Great Cosmic Mother’ 1987.

“Once he has done with the anarchic forces of his own society, man will set to work on himself, in the pestle and the retort of the chemist. For the first time man will regard itself as raw material, or at best as a physical and psychic semi-finished product. Socialism will mean a leap from the realm of necessity into the realm of freedom in this sense also, that the man of today, with all his contradictions and lack of harmony, will open the road for a new and happier race..”

Leon Trotsky – ‘In Defence of the October Revolution’ 1932.

The above quotes inspired me to revive and pursue the development of my political consciousness, hence I am now convinced that providing we can survive global capitalism and replace it with a global socialism, we could enable the emergence of Thomas Berry’s ‘Ecozoic era’, and maybe eventually aglobal communion with the wisdom of Ngapartji-Ngapartji, yet another inspiring indigenous Australian story. Like an onion, as you peal away the layers of this particular Ananguku story it reveals deeper meanings. For example, the outer layers of this story reveal a relatively simple ethic of reciprocity or fair exchange, then maybe that of the ‘golden rule’- doing unto others as they would do unto you. Closer to the core of this Ananguku story reveals a more empathetic relationship whereby we do unto others what they would have us do unto them, a more organic understanding that does not distinguish between receiving and giving, an understanding whereby giving and receiving are one and the same.

Until this day, learning from the place and people of Uluru enables me to continue cultivating a more balanced sense of place and relatedness, it is also enabling in me a deeper spiritual and even political consciousness than I otherwise might have.

All thanks to having found Ngayuku puli tjukurpa – My story stone.

Some of my story telling places

Robert (Taffy) Seaborne

Winter 2021

Southern Hemisphere.

You must be logged in to post a comment.